Do We Owe Delusion More than We Owe Reality?

Evidence shows that forecasting in the social sciences has a large element of delusion. Is that necessarily bad?

Delusion has pros and cons, but it’s not often a choice: We’re wired to bend reality to fit our feelings and urges. If we’re honest, delusion has tricked us into making some of our greatest accomplishments. At least it has for me. It also enables much of an industry: forecasting in the social sciences. Assuming investing is wholesome, is it good or bad if we invest more because of false beliefs?

First, though, a note on something very thankfully non-delusional: I first met Lei 10 years ago, as a guest on her show. There are many things I could say here that I won’t, but for 3.5 years I, like the rest of her friends, wondered if I’d ever see her again. Thankfully, I did, and for kicks we made a point of coming full circle — on her Sky News show. Good things sometimes happen in this life, even after long periods of bad things, and one thing I’ve learned from Lei (2023’s Australian of the Year, and deservedly so) is the importance of savoring them.

In other matters, some locals I met:

Anyway, from my BBAE Blog:

Our 2025 Stock Market Anti-Prediction

“We’ve long felt the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good.”

-Warren Buffett

With 2024 wrapping up and 2025 prediction season in full swing, I’d like to invite you to join me in an anti-prediction tradition: An annual remembrance of the futility of predictions in the social sciences.

Predictions exist because as humans, we value knowing the future.

Well, not quite.

It’s better to say that because knowing the future is hard, and often impossible, what we really value is outsourcing it to someone else.

That’s the true psychic win: Itch scratched, stress and responsibility offloaded.

Early in human civilization, scientific methods were lacking, so fortune telling – which has been practiced for at least 6,000 years, and perhaps longer – stepped in to meet this human need.

Again, the root need isn’t that of accurately knowing the future, despite appearances. Rather, it’s a need for a psychic balm to ease the pain of not accurately knowing the future.

People have made a lot of money by noticing this.

As this former astrologer & psychic implies, even though the Babylonian astrology practised today is based on the Earth-centric model of the universe (discredited 600 years ago by Nicolaus Copernicus – nevermind the fact that the device you’re reading this on is exerting more gravitational force on your body than Jupiter is) it persists because our minds really want it to. Psychics, as the former psychic explains, basically let their customers’ minds do much of the work. Almost all of it, in fact.

If we think of psychics as the pure-play version of this primal human need-meeting, “hard” scientists (even if 2% admit to fudging data and ⅓ admit to questionable research integrity) occupy the other end of the spectrum: proven empiricists. Astronomers are good at forecasting planetary movements, just as meteorologists are decently accurate at predicting near-term weather.

Rigorous empirical feedback loops leave no room for soothsayers.

Or do they?

Enter: the social sciences.

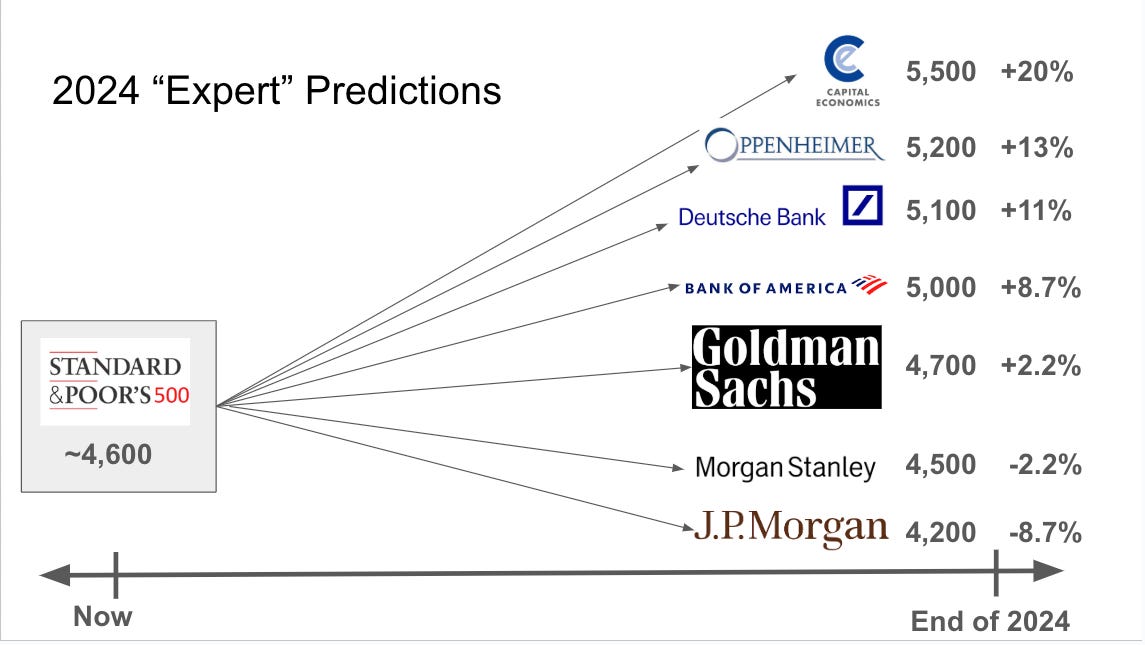

I wrote recently about giving a presentation at the end of 2023, showing the wide range of Wall Street predictions for 2024:

They were all wrong. Wildly so, as Charlie Bilello’s graphic below shows:

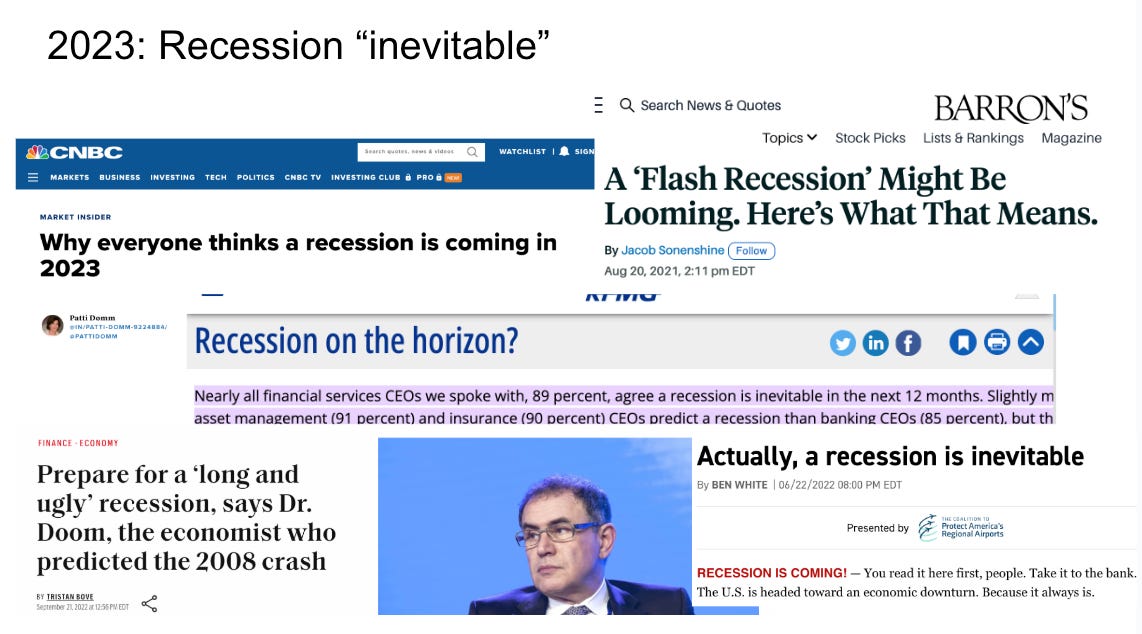

As I also pointed out in my December 2023 presentation, plenty of “experts” – forecasting in 2022 – called for a recession in 2023.

If you missed it, the US stock market and economy alike went on a tear in 2023; the market was up nearly triple its long-term average.

And it’s not just S&P 500 end-of-year price targets that are hard to predict.

Company earnings are hard to forecast, too – it looks more like analysts are better at describing trailing price movement than actually peering into the unknown and coming out with truth in advance of its happening.

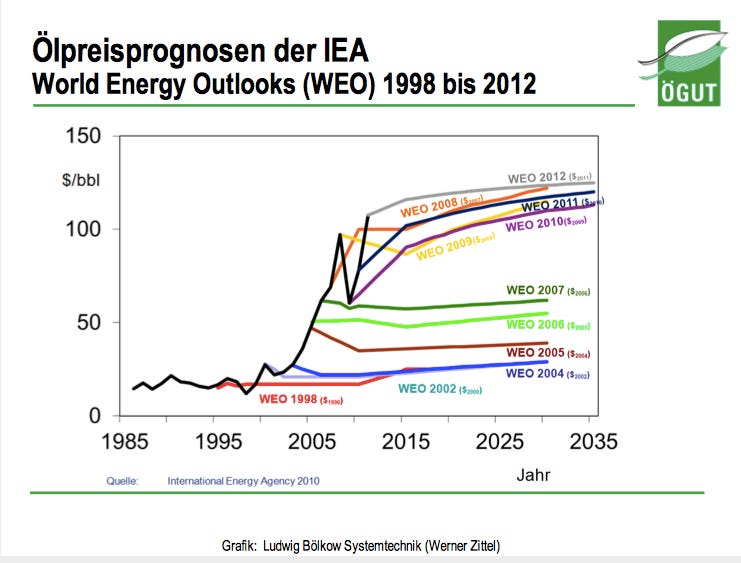

It’s not just an American challenge. This Austrian graph shows that International Energy Agency forecasts look more like simple extrapolations of the status quo going forward – wherever that level happens to be.

The perk of status quo projection is defensibility. If you’re in an ambiguous situation and you’ve got to guess, the status quo is as good a guess as any.

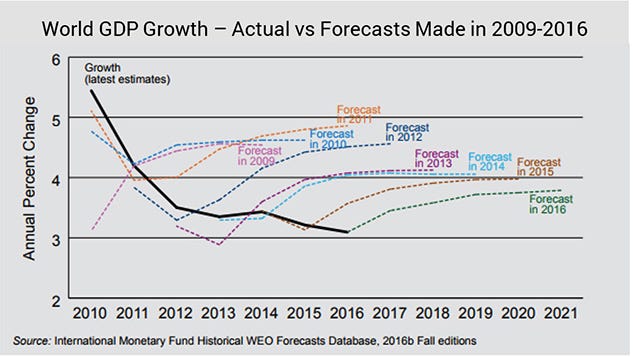

Of course, you’ll miss trends. You’ll be too conservative in an uptrend, like the energy analysts above. And you’ll be too optimistic in a downtrend, per the IMF chart below.

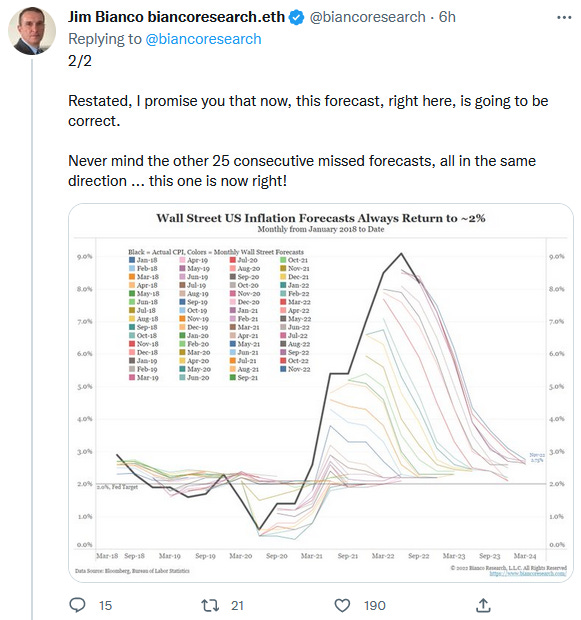

If projecting the status quo ad nauseum sounds too vanilla for you, and you want to deal with trends – and assuming you don’t have any actual ability to forecast whatever you’re forecasting, but want to look like you do – you could either pretend the current trend will continue or, if it’s a thing that mean reverts, just pretend the non-mean-reverting trend ends now, and draw a line making things go back to the mean in some reasonable-seeming period of time.

In a partial defense of the inflation “forecasters,” the further a mean-reverting thing gets from the mean, the more likely mean reversion becomes: If you’re flipping a coin thousands of times, you might get five heads in a row, but not 50. But coin flipping is random and inflation ostensibly isn’t.

An ambiguous future is a scary thing for the human mind. Therefore, the value of a forecaster – aside from the soothing balm stuff, which is probably the majority of a social science forecaster’s value – is to bravely dive into that ambiguity and come back with something useful.

Is that happening here?

No and yes.

I mean, c’mon: I’m open to being shown disproving data, but for the most part, the direct value of numerical forecasts in the social sciences is minimal. I mean, I’d love it if we’d all switched to working 14 hours per week by they year 2000 – a 1965 US Senate subcommittee forecast – but it didn’t happen.

Now, there is an enormous industry – or industries – built around forecasting in the social sciences. Participants feed off each other, perhaps foremost by collectively creating the illusion that if so many smart people have been doing something for so long, it must be legitimate. So it’s useful in a parasitic or economic rent-seeking way, perhaps.

But in an odd recursiveness – a feature, not a bug, of the social sciences – the illusions of certainly and competence peddled by the Wall Street, or City, or wherever-your-market-is apparatus very likely made you, or at least investors like you, comfortable enough to plunk money into the market. Is forecasting an socio-evolutionary illusion with the beneficial side effect of giving us the confidence to do a good thing?

If you’re like me, there are things in life that ended up well, but which you only got into because you had a fully delusional view of reality. If you’d known the real truth about your odds, or the difficulty, or whatever else beforehand, you’d have never tried in the first place.

Almost all of my biggest successes in life came like that. (If so, do I owe delusion more than I owe reality?)

It would make an interesting, and difficult, research question.

Given the fees and given the costs of following uninformed (but informed-seeming) advice, I’m not sure we can easily call social sciences forecasting a net positive for the world, even if it spins off some nice positives.

Let me make a critical point to investors in closing: I’m jaded on social science forecasters, but I’m bullish on investing. I don’t believe in the accuracy of year-ahead price targets for the S&P 500, corporate earnings, or barrels of oil, but I once made my living by running a stock research service – which at least had an element of forecasting to it, in the sense of naming good stocks. (I’ll immodestly add that my service outperformed the market for all 10 years I ran it.)

Many (many) leagues up is Warren Buffett, who may hate stock market forecasters, but who has arguably made a fortune predicting the future in stocks in an non-forecast-y way: In Buffett’s case, as Morgan Housel might say, by betting on business principles and human cognitive biases that are as likely to be present in 10, 20, or 50 years as they are today.

Those factors can be hard to wrap the human mind around. They seem mushy, abstract, and intangible. But they are among the most “real” and enduring reasons to invest.

Meanwhile, a price target of where the S&P 500 will end next year is just an illusion.

Good article as ever thanks James. I think you alude to this, but a point perhaps to add is that there are a lot of mystic-predictioneers that 'get things wrong' who never intended on being right in the first place. For example, an s&p500 prediction of a 20% gain may end up being incorrect when it comes in at a third of that...but if it assisted in driving the price up, or benefitted materially those that were upselling it, then the accuracy was never the goal...sensationalism that drives sales or personal gain was the aim. Looking at the Hillary vs trump image you used is another example. A bought and paid for legacy media shills its own agenda, so reality is less important than the reality (fabricated) they are telling you...in fact the hope is that by telling you loudly and often that up is down, perhaps they will succeed in changing your mind. Would you agree that some of the time, and increasingly much of the time, predictions are not a true reflection of a genuine expectation, rather an opportunity to shill, to sell and to self serve an agenda?